Consent, under the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP Act), 2023, underpins all forms of data processing. In effect, without the consent of a data principal, their data cannot be processed. But is it as simple and straightforward as saying yes? The law makes specific provisions for the kind of consent required, and the manner in which it shall be given. Read on to know everything about consent under the DPDP Act.

The meaning of consent under the DPDP Act

Section 6 of the DPDP Act speaks of affirmative consent and specifies that it should satisfy certain conditions to be tenable under the law:

– It should be free, specific, informed, and unconditional

– It should clearly indicate consent to the action for which consent is requested

– It should agree to the processing of personal data for the specified purpose

This definition is broad and similar to the definition under Europe’s GDPR.

Requirements under the DPDP Act

The primary requirement under the DPDP Act is that data fiduciaries must request consent from data principals before processing their personal data. However, when data must be processed for certain legitimate uses, consent is not required. Section 7 of the Act indicates the legitimate uses for which personal data may be processed without the data principal’s consent, which include employment-related processing, responding to medical emergencies, fulfilling legal obligations on behalf of the state or central government, providing services and benefits to the data principal, and complying with the law.

Whenever consent is sought, it must be accompanied by a privacy notice that contains all the categories of and purposes for which data shall be processed, details on the grievance redressal mechanism, and the method for the enforcement of their rights.

Where a data principal voluntarily gives personal data without indicating non-consent, a data fiduciary does not need to get consent. For instance, adding more information in response to optional form fields while signing up for an account on a social media platform can be considered a case of voluntarily showing data without indicating non-consent.

If consent was given even before the enforcement of the DPDP Act, a data principal must be given a detailed notice with all information on the data collected from them, the purpose of such data collection, their right under the DPDP Act, and the grievance redressal mechanism available to them. Until the data principal withdraws their consent, the data fiduciary can continue processing their data.

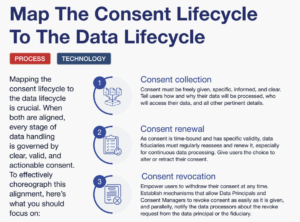

Data fiduciaries must recognise consent managers and enable data principals to entrust them to act on their behalf. The former acts as a single point of contact for data principals, and offers a transparent mechanism to give, manage, review, or withdraw consent. It must be sought each time, for a new purpose of data processing. According to Section 5, each time consent is sought, a detailed notice must be given. Every consent recorded must essentially be accompanied by details of the point in time it was taken, the purpose for which it was sought, the duration, and the method within which it was sought. A data principal always retains the right to withdraw consent at any time, but such withdrawal will not invalidate prior data processing. Data principals have the right to view the notice in any language listed under the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution of India.

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP Act) of 2023 establishes a framework for data protection in India, emphasizing the importance of consent in the processing of personal data. Within this framework, two distinct types of consent are recognized: implicit consent and explicit consent. Understanding the differences between these two forms of consent is crucial for data fiduciaries to ensure compliance with the DPDP Act.

Explicit Consent

This refers to a clear and affirmative agreement from the data principal (the individual whose data is being processed) to allow the processing of their personal data. This type of consent must meet several stringent criteria:

- Clear Affirmative Action: The data principal must take a specific action to indicate their consent, such as checking a box, signing a form, or clicking an “I agree” button.

- Informed and Specific: The consent must be informed, meaning that the data principal is provided with comprehensive information about the data being collected, the purpose of processing, and their rights. It should also be specific to the particular use of data.

- Unconditional: The consent must be given freely, without coercion, and should not be bundled with other consents or conditions.

Explicit consent is typically required for sensitive personal data, where the risks associated with processing are higher. Under the DPDP Act, data fiduciaries must ensure that they obtain explicit consent before processing such data, thereby safeguarding the rights of the data principals.

Implicit Consent

Implicit consent, on the other hand, arises in situations where the data principal voluntarily provides their personal data without explicitly stating their consent. This form of consent is characterized by:

- Voluntary Provision of Data: Implicit consent is assumed when individuals provide their data in contexts where it is reasonable to expect that they would consent to its use. For example, when users fill out a form on a recruitment website, their submission of personal information may imply consent for the platform to use that data for job-matching purposes.

- Limited Scope: While implicit consent may be used in less sensitive contexts, it is generally less robust than explicit consent. The DPDP Act allows for implicit consent in specific scenarios, such as when the processing is necessary for the performance of a contract or when data is provided voluntarily for a specified purpose.

- Conditions for Validity: Even with implicit consent, data fiduciaries must ensure that the data principal is adequately informed about how their data will be used, and they must provide a mechanism for the data principal to withdraw their consent if they choose to do so.

Guardian/Parental Consent: A Special Category

The DPDP Act also gives special consideration to the data of children and persons with disabilities. Under the law, a data fiduciary must seek verified parental consent in order to process the data of a child, and verified consent from a guardian in order to process the data of a person with disabilities who is not in a position to consent for themselves. This is aimed at banning certain practices like targeted advertising aimed at individuals who are not in a position to make free, full, and informed decisions.

In order to collect valid consent for using and processing the personal data of a child, a data fiduciary must:

- Verify whether the user is a child (aged below 18 years);

- Validate the guardian’s identity and age to verify they are not minors themselves;

- Verify the legitimacy of the relationship between the parent and child;

- Collect ‘verifiable’ consent from the parent/guardian;

In order to meet the above guidelines, a data fiduciary must maintain detailed records indicating that they fulfilled these prerequisites in the collection and processing of the data of children and people with disabilities.

Consent Obligations of Data Fiduciaries under the DPDP Act

Any data can be processed only if there is clear, informed, and specific consent from the data principal, with the lone exceptions of state functions and legal obligations. Data fiduciaries are expected, under the DPDP Act, to provide detailed and clear notices at the point of data collection itself, to let the data principal know about the nature of the data collected, the purpose for which they will be processed, and the associated rights. This notice is crucial, as it is central to the data principal being able to exercise their agency over their personal information. Failure to comply with the provisions of the DPDP Act can attract penalties ranging from Rs. 200 to 250 crores.

Watch Now: Processing the DPDP Act: What Data Processors Should Know

FAQs

1. What does consent mean under the DPDP Act?

Section 6 of the DPDP Act specifies that consent should satisfy certain conditions to be tenable under the law:

- It should be free, specific, informed, and unconditional

- It should clearly indicate consent to the action for which consent is requested

- It should agree to the processing of personal data for the specified purpose.

2. Who is responsible for securing consent from the data principal?

The data fiduciary is responsible for this and ensures that the data principal agrees.

3. How is consent secured by a data fiduciary?

A data fiduciary must provide a comprehensive notice detailing the nature of data to be collected and purpose for which it shall be processed, the grievance redressal mechanism for the data fiduciary, and their rights under the law.

4. What are the implications of seeking consent?

Consent once given can be withdrawn or modified. Consent is intended to be specific, which means that once consent is given for data processing for a particular purpose, it cannot be extended to another purpose.

5. Are there any exceptions to consent-based data processing?

Section 7 of the Act indicates the legitimate uses for which personal data may be processed without the data principal’s consent, which include employment-related processing, responding to medical emergencies, fulfilling legal obligations on behalf of the state or central government, providing services and benefits to the data principal, and complying with the law.

6. What happens if data is processed without seeking

consent?

Failure to comply with the provisions of the DPDP Act in relation to consent can attract penalties ranging from Rs. 200 to 250 crores.

7. What is the responsibility of a data fiduciary in relation to

consent over a child’s data?

Under the law, a data fiduciary must seek verified parental consent in order to process the data of a child, and verified consent from a guardian in order to process the data of a person with disabilities who is not in a position to consent for themselves.

8. Who is a data processor under the DPDP Act?

A data processor refers to any individual or organization that handles personal data on behalf of a Data Fiduciary.

9. Who is a data fiduciary under the DPDP Act?

A data fiduciary is any person or organization that, either independently or together with others, determines the reasons and methods for processing personal data.

10. Who is a significant data fiduciary under the DPDP Act?

A Significant Data Fiduciary is a specific data fiduciary or a group of data fiduciaries, designated by the Central Government under Section 10 of the DPDP Act.

11. What responsibilities does a data processor have under the DPDP Act?

A data processor is tasked with processing personal data on behalf of data fiduciaries for the specific purposes for which consent has been obtained.

12. What responsibilities does a data fiduciary have under the DPDP Act?

In the event of a personal data breach, the data fiduciary must immediately notify both the Data Protection Board (DPB) and the affected individuals, detailing the breach and steps taken to mitigate the impact. Additionally, Data Fiduciaries must ensure that personal data is erased once the data principal withdraws consent or when the data is no longer needed for its intended purpose.

They must also ensure their data processors erase any data shared for processing. When personal data is used for decision-making or shared with another data fiduciary, it is the processing fiduciary’s responsibility to verify the data’s accuracy, completeness, and consistency. Personal data can only be processed for lawful purposes, either with the Data Principal’s consent or under specific legitimate grounds.

13. Can an entity act as both a data fiduciary and a data processor?

Yes, an entity can serve as both a data fiduciary and a data processor, depending on the role it plays in relation to the personal data of the data principals.

14. Does the DPDP Act apply to cookies?

As of now, there is no clear provision for cookies under the DPDP Act. However, this might be applicable if cookies are deemed to contain “personal data,” which the Act defines as any information that can directly or indirectly identify an individual. Since cookies can track and store data related to browsing behavior and potentially link back to individuals, there is a strong possibility that they would fall under the scope of “personal data.”Over time, case laws or judicial interpretations could offer more clarity on how cookies are treated.

The focus will likely be on whether the data collected through cookies qualifies as personal data and whether appropriate consent was obtained from the user. For online businesses, this implies the need to ensure their cookie practices are compliant. They should implement transparent consent banners, allowing users to easily accept or reject cookies while ensuring that any consent gathered is informed, specific, and freely given. Using consent management tools can also help streamline compliance by tracking and managing user consent effectively.

15. What are the key differences between the DPDP Act and GDPR?

The DPDP Act and the GDPR share similarities in providing individuals with fundamental rights concerning their personal data, such as access, modification, and deletion. Both frameworks emphasize safeguarding data privacy and include enforcement mechanisms to address non-compliance.

However, there are notable differences between the two:

Scope of Applicability: While the GDPR covers personal data organized as part of a filing system, the DPDP Act applies to data collected both digitally and offline, provided it is later digitized.

Obligations on Entities: Under GDPR, both data controllers (fiduciaries) and processors have obligations, although controllers bear more responsibility. In contrast, the DPDP Act places all responsibility on data fiduciaries, who must ensure that data processors also comply with the law.

Consent Managers: The DPDP Act introduces consent managers, a feature absent in the GDPR.

Consent Requirements: GDPR mandates consent from individuals regardless of whether the data is publicly available. The DPDP Act allows for the processing of publicly available data without explicit consent.

Legitimate Use Cases: The DPDP Act has a more limited definition of “legitimate use cases” compared to the GDPR, making consent essential for more situations.

Data Subject Rights: While both laws grant similar rights, the DPDP Act offers the right to correct data, and the GDPR uniquely grants the right to data portability.

Notification of Data Breaches: GDPR requires organizations to notify affected individuals of data breaches within 72 hours and fulfill Data Subject Access Requests (DSAR) within 30 days. The DPDP Act imposes these obligations but without specific time frames.

Parental Consent for Minors: The GDPR mandates this for processing data of minors under 16 (with member states allowed to lower this to 13). The DPDP Act sets the threshold at 18 years.

Data Localization: GDPR enforces strict data localization rules, requiring data to be stored within the EU. The DPDP Act is less rigid on this aspect.

Penalties: Severe GDPR violations can result in fines of up to €20 million or 4% of global turnover, whichever is higher. The DPDP Act imposes penalties of up to INR 250 crores, depending on the nature of the violation and the measures taken toward compliance.

16. What is the difference between PII and personal data?

The definition of personal data or PII varies significantly depending on the country. Different countries even use distinct terminology in their respective data privacy regulations. For instance, in the U.S., the term “Personally Identifiable Information” (PII) is commonly used in data protection laws, whereas the GDPR in Europe uses “personal data” to describe a similar concept, but with a broader and more internationally recognized scope.

While all PII is considered personal data, not all personal data qualifies as PII, especially under more stringent legal frameworks.

Definitions and categorizations depend on the specific laws and regulations in different regions. Below are the definitions according to the GDPR and CCPA:

Personal Data: Under the GDPR, personal data refers to any information relating to an identified or identifiable individual (referred to as the data subject). This includes common identifiers like names, addresses, and ID numbers, as well as characteristics tied to a person’s physical, genetic, mental, economic, cultural, or social identity.

Personally Identifiable Information (PII): According to the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), PII is defined as “information that identifies, relates to, describes, is capable of being associated with, or could reasonably be linked, directly or indirectly, with a particular consumer or household.”

17. Are medical records PII data?

Yes, medical records and diagnostic reports are considered PII (Personally Identifiable Information). In fact, they are often classified as sensitive PII or sensitive personal data, depending on the legal framework. This is because these records contain information that directly relates to an individual’s health and can identify or be linked to a specific person.

For example:

Under GDPR (Europe): Medical records and diagnostic reports are categorized as special categories of personal data or sensitive personal data, which require stricter protection measures. This includes information about a person’s physical and mental health, as well as genetic and biometric data used for medical purposes.

Under HIPAA (U.S.): The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) protects Protected Health Information (PHI), which includes medical records and diagnostic reports. PHI is a subset of PII that specifically applies to health-related information linked to an individual.

Under CCPA (California): Health-related data, including medical records, also falls under the definition of PII, especially when it can be linked to a particular consumer or household.

Because of the sensitive nature of health data, laws governing it often impose additional security requirements and restrictions on how it can be collected, processed, and shared.

18. What is considered as ‘personal data’ in India?

In India, personal data refers to any information that can identify an individual, either directly or indirectly. This definition aligns with the principles outlined in the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP Act) 2023 and other regulatory frameworks.

Some key examples of personal data include:

- Basic Identifiers: Name, address, phone number, email address, etc

- Government Identifiers: PAN (Permanent Account Number), Aadhaar number, passport number, driving license, etc.

- Financial Information: Bank account details, credit/debit card numbers, transaction histories

- Online Identifiers: IP addresses, device identifiers, cookies, etc

- Sensitive Personal Data: This includes health records, biometric data (fingerprints, retina scans), sexual orientation, political or religious beliefs, and more

- Location Data: Information that can track someone’s location in real-time or through history

The DPDP Act also categorizes personal data into general and sensitive personal data, the latter of which requires stricter protection and regulatory compliance.

IND

IND ID

ID PH

PH