The DPDP Rules: Decoding India’s New Data Protection Law

Table of Contents

What is the DPDP Act?

The DPDP rules are supplementary guidelines to enforce the DPDP Act and the privacy law protection mechanism as a whole. In effect, the DPDP Act and DPDP rules apply to Indian residents and businesses that collect and process the data of Indian residents and to non-citizens living in India, whose data processing “in connection with any activity related to the offering of goods or services” happens outside India.

For instance, when a Canadian citizen living in India receives digital goods and services within India from an Australian provider, the Australian provider is covered by the DPDP Act. Thus, the act also applies extraterritorial.

In principle, the DPDP Act 2023 is aimed at striking a balance between the recognized need to process personal data for a variety of purposes on the one hand, and the individuals’ right to control and protect their data, on the other hand. The DPDP Rules bring the legislation to life by guiding their implementation.

Further, the Act also allows for specific legal bases for data processing aside from the consent of the owner of the data (or the data principal). However, consent is fundamental for most purposes of data processing.

In summary, the DPDP Act and DPDP rules strive to establish a higher threshold of accountability and responsibility for all those operating within India, including both internet and mobile app companies, and any business involved in the collection, storage, and processing of citizens’ and resident non-citizens’ data.

When will the DPDP Rules come out?

The DPDP rules are anticipated to be published soon. After their release, the DPDP rules will be subject to public consultation.

In an interview with Moneycontrol, IT Ministry Secretary S Krishnan highlighted that releasing the notification on the DPDP rules for the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act is top priority now.

What can we expect from the DPDP Rules?

The DPDP rules might outline:

- Exemptions for children’s data processing: The government could allow exceptions for educational institutions, healthcare providers, and certain public entities from the strict requirements around processing children’s data as outlined in the DPDP Act.

- Data breach notification: Any platform, whether operated by the private or public sector, that processes personal data would be required to promptly inform the Data Protection Board (DPB) upon discovering a data breach.

- Responsibilities for obtaining consent: Platforms handling the personal data of children or individuals with disabilities will bear the responsibility of ensuring parental or guardian consent is properly obtained. Verification of consent may need to be supported by government-issued IDs.

Overview of the DPDP Act

A broad overview of the DPDP Act, 2023 is as follows:

Applicability: The DPDP Act applies to Indian residents and businesses that collect and process the data of Indian residents. It also applies to non-citizens living in India, whose data are processed, in connection with any activity related to offering goods and services, outside India.

Purposes of Data Collection and Processing: The DPDP Act allows for the processing of personal data for any lawful purpose. The data can be processed either on the consent taken from the data principal or for legitimate uses as explained by the act. Consent must always be free, specific, informed, unconditional, and unambiguous with clear affirmative action, and for a specific purpose.

Data collected must be limited to all that is necessary for the specific purpose. Data principals must be given a clear notice containing all these details and their rights under the law. Once given, consent can be withdrawn at any time.

The law defines legitimate use to include situations:

- Where an individual provides personal data for a specific purpose

- Involving the provision of any subsidy, benefit, service, license, certificate, or permit by any agency or department of the Indian state, provided that the individual has consented to receiving any other such service from the state

- Concerning the sovereignty or security of India

- Involving the fulfilment of a legal obligation to disclose information to the state

- Concerning compliance with judgments, decrees, or orders,

- Of medical emergency or threat to life or epidemics or threat to public health

- Of disaster or breakdown of public order.

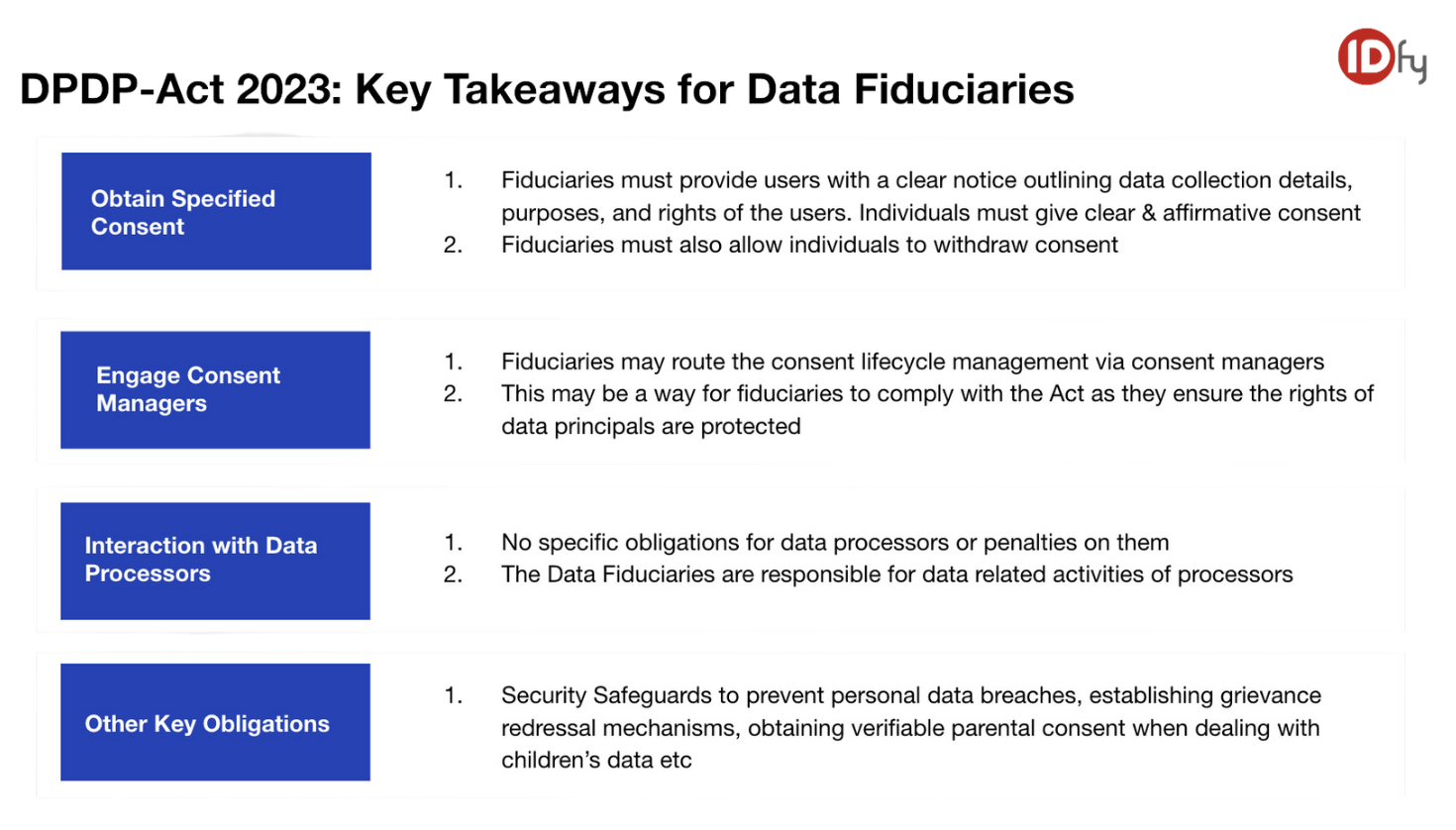

Rights of Users and Obligations of Data Fiduciaries: The DPDP Act prescribes particular rights for users and consumers of Data-Related Products and Services, and creates related obligations as a corollary for data fiduciaries. These details are listed under the sections dedicated to each category of actors.

Significant Data Fiduciaries (SDFs): The creation of SDFs, who are to be designated by the government based on certain criteria, such as the volume and sensitivity of data and risks to data protection rights, sovereignty and integrity, electoral democracy, security, and public order. SDFs will have additional obligations such as appointing a data protection officer, conducting data protection impact assessments and audits, and taking other measures as prescribed by the government.

Exemptions from Consent and Notice Requirements: The DPDP Act also provides exemptions from consent and notice requirements and other obligations of data fiduciaries and related requirements where:

- Processing is essential to enforce any legal right or claim

- Personal data has to be processed by courts or tribunals, or for the prevention, detection, investigation, or prosecution of any offences

- Personal data of non-Indian residents is being processed within India.

Establishment of the Data Protection Board (DPB): The DPDP Act establishes the DPB, which has a limited mandate to oversee the prevention of data breaches and direct remedial action and to conduct inquiries and issue penalties for noncompliance with the law. It does not have any powers to frame regulations or codes of conduct or to call for information to supervise the workings of businesses. It can only do so during the process of conducting inquiries. The members of the DPB shall be appointed by the government and shall be governed by the terms and conditions of service as prescribed by the government in its rules.

Monetary Penalties for Violations: The DPDP Act empowers the Data Protection Board to impose monetary penalties of up to INR 250 crores for violations. Organizations can appeal the Board’s decisions to the Telecom Disputes Settlement and Appellate Tribunal (TDSAT).

Compliance with the DPDP Act is mandatory, with non-compliance leading to significant penalties. Violations of privacy rules may result in fines of up to INR 1 lakh for individuals and up to INR 10 lakhs for companies.

Penalties for overall non-compliance under the DPDP Act range from INR 10,000 to INR 250 crores, depending on the severity and nature of the violation.

Blocking Access to Information: The government, based on a reference from the DPB, can also block the public’s access to any information that enables a data fiduciary to provide goods or services in India, and this is based on two criteria: the board has imposed penalties against such data fiduciaries on two or more prior occasions, and the board has recommended a blockage. The data fiduciary must be given an opportunity to be heard before such action is taken.

Upcoming DPDP Rules: The DPDP rules, at the time of writing, are to be released soon for public feedback and inputs, according to the Minister of I&B, Railways, and MeitY, Ashwini Vaishnaw.

Similarities between GDPR and the DPDP Act

Both the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) and the DPDP (Digital Personal Data Protection) Act offer essential rights to individuals concerning the protection of their personal data.

These similarities include:

- Individual Rights: Both regulations grant individuals the right to access, modify, delete, or rectify their personal data.

- Respect for Data Privacy: Data privacy rights are a priority under both the GDPR and the DPDP Act, and organizations must respect and uphold these rights.

- Enforcement and Penalties: Both laws establish mechanisms for enforcement and impose penalties on organizations for non-compliance.

Key Differences Between GDPR and DPDP Act

| Aspect | GDPR | DPDP Act |

| Applicability | Applies to personal data that forms part of a filing system. | Applies to personal data collected digitally or offline and later digitized. |

| Obligations on Controllers and Processors | Data controllers (fiduciaries) and processors have obligations, with controllers bearing more responsibility. | Data fiduciaries are responsible for all obligations and must ensure processors comply with the DPDP Act. |

| Consent Managers | No provision for consent managers. | Introduces the concept of consent managers to help manage data consents. |

| Publicly Available Data | Consent is required even if the data is publicly available. | Publicly available data can be processed without explicit consent. |

| Legitimate Use Cases | Broad definition of legitimate use cases where consent is not required. | Narrower definition of legitimate use cases; beyond these, consent is required for data processing. |

| Rights of Data Subjects | Includes the right to data portability. | Includes the right to correction of data (but not portability). |

| Data Breach Notification | Organizations must notify individuals within 72 hours of a data breach. | Notification is required but no specific time limit is imposed. |

| Parental Consent | Required for minors under 16 (with some countries lowering it to 13). | Required for all minors under 18 years old. |

| Data Localization | Mandatory to store customer data within the EU. | No stringent data localization requirement. |

| Fines and Penalties | Fines up to €20 million or 4% of global turnover, whichever is higher. | Fines up to INR 250 crores depending on the nature of the violation and steps taken to comply. |

Who is a Data Principal?

A data principal is the individual whose data is gathered and processed. They are effectively the data subject. For example, when a person submits their full name, temporary and permanent address, age, and relevant documentation to a healthcare provider, this person is the data principal. The DPDP Act is intended to protect the data of the data principal.

Under the DPDP Act, a data principal has the right to:

- Access their personal data held by data fiduciaries, including the source of the data, the purpose for which the data is being processed, as well as the categories of data recipients.

- Correct their personal data, if it is inaccurate, incomplete, or incoherent.

- Erasure of their personal data. A data principal can decide if they want to have their personal data erased if they find that it is no longer necessary for the purpose for which it was collected or processed, and if they withdraw their consent to processing and collection.

- Restrict the processing of their personal data in particular circumstances, and a data fiduciary and processor must honour this decision.

- Data portability, meaning that they can obtain a copy of their personal data in a structured, machine-readable format that is commonly used. They also have the right to transmit that data to another data fiduciary.

- Object to the processing of their data for certain purposes through the formal channels of the data fiduciary or through a legal route.

- Withdraw consent at any point in time, which makes it mandatory for the data fiduciary to comply and to stop collecting and processing data from that particular data principal.

Insights from industry leaders

“When data protection laws were initially being conceptualized, there was a lot of focus on the data fiduciary being fully responsible, even if data was passed down to second, third, or even fourth processors. The idea was that the data fiduciary should remain the primary point of contact for the data principal. While this makes sense in theory, in practice, it can be incredibly challenging for a data fiduciary to keep track of all the downstream processors. Still, that’s the approach the law currently takes.”

Supratim Chakraborty

Partner at Khaitan & Co.

Who is a Data Processor?

A data processor is responsible for processing digital personal data on behalf of a data fiduciary. Broadly, they are of two categories of data processors. Non-customer-facing and customer-facing data processors. The former processes personal data shared by a data fiduciary, and not directly by a data principal.

For example, card printing companies and logistics companies that deliver those cards, as well as marketing technology companies that send OTPs and email notifications. The latter processes personal data directly from the data principle. For example, v-KYC companies and white labeled platforms.

To get a better understanding of what data processors should know about their duties under the DPDP Act, watch the full webinar below!

You can also read this document which contains all the points that were discussed in the webinar.

Who is a Data Fiduciary?

A data fiduciary is an entity that, either independently or in collaboration with others, establishes the purpose and methods for processing personal data. In effect, this entity is similar to a data controller. Under the DPDP Act, a data fiduciary may be classified as a Significant Data Fiduciary, if their processing activities (such as the volume and sensitivity of personal data involved and the impact on the rights of data principals) relate to larger social and national concerns such as India’s sovereignty and integrity, electoral democracy, state security, and public order.

If a data fiduciary is classified as an SDF, there are additional obligations imposed on them – such as appointing a Data Protection Officer (DPO) responsible for addressing the inquiries and concerns of data principals. The government may impose restrictions on an SDF from time to time, through notifications.

The data fiduciaries are responsible for

- Maintaining security safeguards

- Ensuring completeness, accuracy, and consistency of personal data

- The intimation of data breach in a prescribed manner to the Data Protection Board of India (DPB)

- Data erasure on consent withdrawal or on the expiry of the specified purpose

- The data fiduciary having to appoint a data protection officer and set up grievance redress mechanisms

- Consent of the parent/guardian being mandatory in the case of children/minors (those under eighteen years of age).

Further, any data processing that is likely to have a detrimental effect on a child is not permitted. The law prohibits the acts of tracking, behavioral monitoring, and targeted advertising directed at children. The government can prescribe exemptions from these requirements for specific purposes.

Can a data processor be a data fiduciary and vice-versa?

Under the DPDP Act, a pertinent question that may emerge is the distinction between the data fiduciary and data processor, and whether they might be the same entity at all. In principle, the data fiduciary is the one who determines the purpose and means of processing personal data collected, and the data processor is the one who processes the data on behalf of the data fiduciary.

There is a tendency to assume that the data fiduciary alone has obligations under the DPDP Act and that the data processor does not. This assumption has given room for data fiduciaries to find ways to stretch the definition of a data processor to accommodate them within its scope. However, under the law, as personal data privacy is the core focus, a data processor can be implicitly understood to have a responsibility to verify consent, respond to data deletion and updation requests, and to maintain a clear repository of PII data and consent received for each item gathered and for the purpose for which it is gathered. While the law may not mandate this in as many words, it is a good practice to build this commitment to the privacy ecosystem in order to ensure transparency.

Insights from industry leaders

“Eventually, every entity will play the role of a fiduciary. From the moment a company is set up, it begins collecting data—whether from workers or other stakeholders. So, initially, a company is a fiduciary. Then, as it starts serving other clients or companies, it may also become a processor. Essentially, every company has to comply with all relevant regulations, whether it’s the GDPR, DPDP, or any other law, because everyone eventually handles personal data in one way or another.

But to address the question about customer-facing and non-customer-facing processors—while that categorization is one way to look at it, I believe that, in the end, both types of processors are acting on behalf of another party. For example, if I outsource my website hosting to a third party, the end user only sees my company. The fiduciary, in this case, is the one with the direct relationship to the consumer, and the consumer is unaware of the processors working behind the scenes.

That’s important because when it comes to consent, the processor cannot collect consent on their own. The role of obtaining and managing consent falls to the fiduciary. Different sectors have different obligations—take banking as an example, where the RBI requires data retention even after account closure. However, the processor cannot retain consent details for the required 10 years. Therefore, the responsibility for consent management should remain with the fiduciary.

In agreements between fiduciaries and processors, it’s essential to clearly define these responsibilities. Shifting consent management to the processor isn’t practical, as it adds complexity and makes rigorous consent management unfeasible for them. Instead, the fiduciary should handle consent collection and retention for all parties involved. For instance, if a bank works with multiple processors, the fiduciary should be the one managing consent across the board, ensuring clarity and consistency for everyone.”

Kishore Manvuri

DPO at Jio Haptik

What is Parental Consent and the Right to Nomination under the Act?

Under the DPDP Act, the personal data of a child and of persons with disabilities cannot be processed without the consent of their parents or lawful guardians. To collect valid consent for the use of a child’s personal data, it is essential to verify whether the user is a child or a person with disabilities, to validate the guardian’s identity and age to ensure that they are not minors in themselves, to verify the legitimacy of the relationship between the parent and child, and to collect verifiable consent from the parent or guardian. It is essential to maintain detailed records demonstrating the fulfilment of these prerequisites to meet the threshold of verifiable consent. Under the DPDP Act, the data fiduciary is responsible for ensuring that the user is not a child.

The DPDP Act bans any data processing that can produce a detrimental effect on the well-being of children. The term ‘detrimental effect’, however, has not been defined under the law, but can be interpreted to mean consequences that comprise a child’s privacy, security, health, and well-being. The DPDP Act also prohibits tracking and monitoring children and targeting them with advertisements.

As of now, the government has reserved the power to notify exceptions to the DPDP Act concerning children’s consent in relation to particular classes of data fiduciaries to whom the obligations will not apply (e.g., educational and healthcare providers); specific purposes of processing that will be exempt (e.g., child welfare and academic purposes); and a lower age for applicability of the rules on parental consent and tracking in certain contexts.

What is PII Data?

The DPDP Act considers any data of an individual that can be potentially used to identify that individual their personal data. Public information does not fall under the scope of personal data. Any information published by the data principals themselves or authorized government agencies is considered public information. All personal data published to a specified audience or not published anywhere is protected as personal identifying information.

What is required for designing consent notices?

The DPDP Act requires all privacy notices and requests for consent to be accessible in English and in all languages listed under the 8th Schedule of the Constitution of India. Any notice provided should be clear, accessible, and easy to understand. Data fiduciaries must issue privacy notices alongside every request for consent, which should contain the categories of personal data collected, the purposes for which personal data is collected, the process of exercising consumer rights, the procedure to revoke consent, and the procedure to file complaints with the data protection board.

What does the DPDP Act say about Cookies?

Cookies refer to data stored on a user’s device, which allows the website storing such data to identify and profile the user at a later date. The DPDP Act does not explicitly designate cookies as personal data, although it is possible that cookies can be considered thus – essentially because the data helps identify the individual, which is the definition of personal information under the act. This may mean that online businesses will have to revamp their websites to offer proper and compliant consent banners to continue operating and using their cookies.

Who is a Data Protection Officer (DPO)?

The DPDP Act requires Significant data fiduciaries to appoint a contact person, known as the Data Protection Officer, to address questions that a data principal may have about the processing of their personal data. DPOs must be based in India and shall be responsible to the board of directors or any similar governing body of the data fiduciary. DPOs will also be the point of contact for a data principal for the redressal of any grievance under the DPDP Act.

What is a Consent Artifact?

A consent artifact is a digital, machine-readable record that helps manage consent. It includes:

- Information identifying both you (data principal) and the business (data fiduciary)

- The specific purpose for data processing

- A unique identifier for the consent record

- Electronic signatures

- The consent artifact allows for easy tracking of consent actions, like giving or withdrawing consent.

A possible way to operationalize the orchestration of appropriate notices relevant to a compliant digital interaction is leveraging a consent artifact, an immutable, machine readable electronic record that stores consent information throughout the course of its validity period. It is expected that the consent artifact shall need to be built on top of MeiTy’s Electronic consent framework, therefore containing appropriate signatures of the data principal and the data fiduciary. This shall enable it to be admissible in a court of law.

FAQs on the DPDP Act and DPDP Rules

Yes, the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP Act) has been passed in India. It establishes regulations for the protection of personal data and governs how organizations handle and process personal data to ensure privacy and security compliance.

Under the DPDP Act, penalties can be significant. Depending on the nature and severity of the violation, organizations can be fined up to ₹250 crores (approximately 30 million USD). Fines are imposed for non-compliance with data protection requirements, improper data handling, and unauthorized data breaches.

The Data Protection Board of India is responsible for enforcing the DPDP Act. This authority oversees compliance with the Act, manages grievances, and has the power to impose penalties and ensure organizations follow the regulations related to data protection.

A consent notice informs individuals (data principals) about how their personal data will be processed. This helps them make an informed decision before they provide consent for data collection and processing.

Personal data collected could include:

- Name

- Email address

- Credit card details

- Home

address

The specific data being collected is always mentioned in the notice, so you know exactly what information is being requested.

Businesses collect personal data for various purposes, such as:

- Name and email to register your account

- Credit card details to process payments

- Address

to deliver goods

Each piece of data is collected for a clear reason, which is detailed in the consent notice.

The retention period depends on the type of data. For example:

- Your name and email might be kept as long as you remain a customer.

- Credit card information will be kept until your payment is processed.

- Address details are retained until the goods are delivered. Once the purpose is fulfilled, the data is erased unless there’s a legal reason to keep it.

Yes, you can withdraw your consent at any time. Most businesses provide an easy way to do this, like a link in an email or on their website. Once withdrawn, your data will be erased unless there’s a legal requirement to keep it.

If you have any concerns or questions about how your data is processed, there’s usually a contact link provided in the notice. This allows you to reach out to the business directly for clarification.

If you have a grievance, the consent notice should direct you to a link where you can register your complaint. If the business doesn’t respond within a certain timeframe (e.g., 72 hours), you can escalate your complaint to the Data Protection Board of India.

A consent manager is a platform that helps you give, manage, review, or withdraw your consent. They ensure that your personal data is securely shared between businesses, without accessing the data themselves. They are required to operate transparently and are subject to strict obligations under the DPDP rules.

If a business experiences a data breach, they are required to inform the Data Protection Board within 72 hours. Additionally, you will be notified with details about the breach, including the nature of the breach, the timing, and steps to mitigate risks. You’ll also be informed about any measures you should take to protect yourself.

The DPDP Act aims to build trust between businesses and individuals by ensuring that personal data is handled responsibly and transparently. Compliance with the Act’s guidelines shows that a business values privacy and protects your data, which in turn fosters trust and accountability.